Airborne

Elina Frumerman

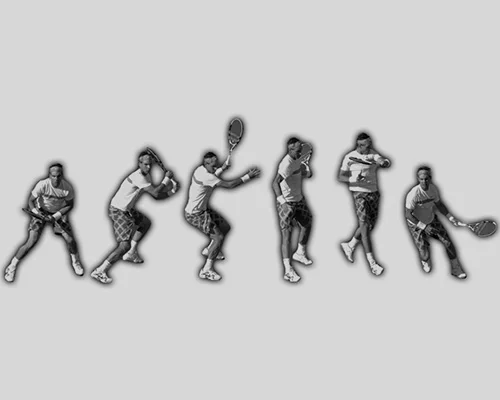

Breaking down Rafael Nadal and Andy Murray's gravity-defying shotmaking

The days when stroke production meant stop, plant, turn and step are long gone. Today’s tennis is increasingly untethered to the ground, especially on the forehand side. Players launch themselves into shots and create extreme rotation. They position themselves for higher bouncing balls — a result of today’s spin-heavy strings. But the elevation isn’t always what it seems. We asked two experts to break down the gravity-defying shotmaking – John Yandell, researcher and owner of tennisplayer.net, and Todd Ellenbecker, senior director of medical services for the ATP Tour.

RAFAEL NADAL

Nadal sets himself up with flexion: His ankles are dorsi-flexed (when his toe rises up) tensing his calves; his knees bend, putting his quadriceps into a stretch. His glutes activate due to flexion of his hips. He is in a position to prepare for explosive force production in the upcoming shot.

He moves to his left in a semi-crouched position with both hands on the racket. The body turn provides most of the preparation for the acceleration phase of swing.

With his racket back, he begins acceleration with his arm and transfers energy from his lower body to his trunk and ultimately into his shoulder and arm.

His left leg drives him off the court, transferring energy to his hips and shoulders. The intense shoulder-hip separation optimizes lower and upper trunk force.

The accumulated rotational forces in his lower body send him into the air as if he were jumping off the ground.

He lands on his left leg and immediately pushes off to prepare for the next shot in a crouch position.

Nadal often leaves the ground to strike his whipsaw forehand; the accumulation of forces he imparts into the court and through body rotation cause his lift.

ANDY MURRAY

Murray split steps with his left foot pointed in the direction of his movement (left), while his right foot is planted straight ahead.

His body rotation initiates the backswing as he prepares to strike the ball.

His shoulders rotate further than his hips, creating the desired hip-shoulder separation which optimizes trunk rotation and racket-head speed.

Pushing off the ground with his back foot and rotating with his upper body launches him into the air – not so much a jump as a summation of lower- and upper-body forces.

He lands on his right leg and appears to be moving forward and towards the net.

His recovery step comes off the left leg to bring himself forward, and he begins another split step, semi-crouched to the ground.

Murray is one of the more balanced players on tour, but the power of his plant and rotation often sends him upward. The stability of two hands on the racket means less air time for most players compared to the forehand.