Fake Apology

Elina Frumerman

WIMBLEDON, England – At tradition-bound Wimbledon, officials show little leeway with the strict dress code (white only) and once requested players to bow and curtsy before Center Court's Royal Box.

But when it comes to another hackneyed custom – the phony apology -- the All-England Club's policy police let the sport's social mores dictate.

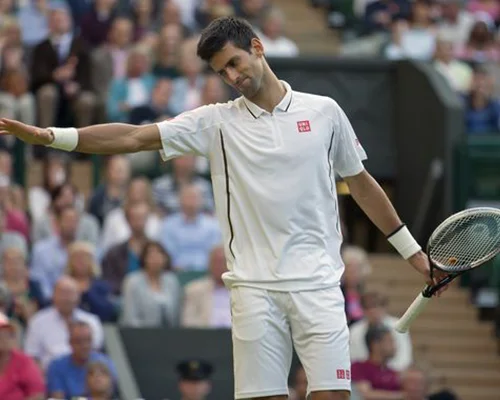

Often, when a player hits a lucky net-cord or a framed shot out of reach, they offer a repentant hand.

Usually it's a slight wave, sometimes accompanied with a flick of the racket. A player might also offer acknowledgement with a gesture, a gaze or a regretful expression before the next point.

Though ingrained in tennis' culture, nobody means it.

"You're never sorry," says Bob Bryan. "You're actually kind of elated that you got the luck."

"It's a total scam," says broadcaster Mary Carillo.

In other sports, the luckiest outcomes elicit zero contrition – and usually rapturous celebration.

A broken bat single? A slapshot that deflects into the net? A fumble at the goal line? An own goal in soccer?

Nobody apologizes sorry for these fortuitous turns of fate. In tennis, even the most notorious bad actors are programmed to say sorry, making it one of sport's strangest, and bogus, unwritten rules.

"I do it most of the time because it's normal," says Fabio Fognini, the Italian who has racked up a Grand Slam record $29,500 in fines for his boorish behavior at Wimbledon.

The origins remain unclear. Most players past and present can't identify where or how they picked it up. Largely, it seems, by competitive osmosis.

Ana Konjuh, the rising 16-year-old star from Croatia, waved a few apologies when some of her crafty shots nicked the net and fell over for winners in a loss last week to Caroline Wozniacki.

"Since I was young they told me to do it," said Konjuh.

Most agree it stems from the British "genteel manners" era from which games like golf and lawn tennis were born.

"You know, 'Jolly Good Sport' and all that'," says Bud Collins, the tennis historian.

Barry Davies, the longtime BBC sports commentator, said he had no idea where it originated but likened it to the days when men would tip their hats to ladies when they passed on the street.

"I'm tempted to wonder what happened to soccer because we invented that, too," Davies, 76, said.

Others trace it to the individual nature of tennis where competitors face off in close proximity.

In truth, its use is situational. Some say it's only appropriate on a crucial point. Others take the opposite tack and say they are more likely to offer a gesture of sympathy if they are beating an opponent badly.

Friends tend to do it to each other. Enemies don't.

"I don't do it if the guy's being an (expletive)" said 41-year-old doubles specialist Daniel Nestor of Canada.

Some only offer a fake signal of regret when scrutinized by a large audience, giving new relevance to the meaning "show court."

"I say sorry so that people don't think I'm mean," said Liezel Huber, a former top-ranked doubles player.

The USA's Huber believes peer pressure and fear of public retribution creates an absurd double standard for something nobody buys.

"I think it's unfair when you get critiqued for not saying you're sorry because I truly don't think anybody is sorry," she said. "It's not like a sign of common courtesy like thank you, please, hello. Those things you have to do in life. But this, you don't have to do it. This is an extra bonus. But when you don't do it, you get bullied for it."

Perhaps no player is better positioned to opine on the subject than Roger Federer. The 17-time Grand Slam champion from Switzerland has won the ATP Tour's sportsmanship award a record nine times.

Federer says it can be overwrought, doesn't always do it, and admits he sometimes mocks the custom in practice.

"Oh, I'm so sorry man, I hit that net cord," the Swiss laughed when describing the fake apologies he issues in training.

In matches, Federer says he communicates contrition with a stare before the next point – "eye contact and a little gesture, tiny, but the opponent knows I meant it," he says.

Still, the decorum-conscious Swiss calls it "classy," and "expected" even if a lucky winner is such a "small part of the puzzle" during a match that it's not really necessary.

"I think it's a bit exaggerated to do it every single time," he says.

Few get annoyed if their opponent doesn't do it. A fair number think it is a nice tradition, even if they could care less.

"It's an unspoken rule," said Denmark's Wozniacki. "Tennis is a fair-play game just like golf."

Like it or not, observers say the practice is in decline, buffeted by the sport's big-money stakes and the flourishing landscape of fist pumps, self-exhortations and inward-focused mannerisms. Most say they don't bother to look at their opponent anyway.

Which is fine, since to many it's an antiquated, disingenuous and largely unnecessary relic of the past.

"It's aggressively insincere," says Carillo. "We could probably do a fade on it and no one's going to miss it."

"It's just been part of our culture," says women's tennis pioneer Billie Jean King, who wouldn't mind if it went away.

Russia's Maria Sharapova, however, says it serves a purpose.

The reigning French Open champion with the steely mentality has her reasons for why it should stick around.

"I'm sorry," she said, "because I'd rather have finished it on a outright winner."