Occupy Tennis?

Elina Frumerman

INDIAN WELLS, Calif. – When billionaire owner Larry Ellison offered to sweeten the pot for this year's BNP Paribas Open— boosting the singles winner's check to a cool $1 million — it appeared to be prize-money manna from heaven.

But Ellison dangled his dough with strings attached.

The take-it-or-leave-it deal stipulated that his extra $700,000 would go to the final three rounds, from the quarterfinals on (a much smaller portion would go to doubles).

The winner's check would thus jump 64% from $611,000 to $1 million from the previous year. By contrast, first-round losers would pick up $7,709 instead of $7,115, a $594 bump equivalent to 8%.

That put the ATP World Tour in a squeeze. Take Ellison's money, and earlier rounds would be shut out. Turn it down, and deny income to players.

In the end, the tour accepted Ellison's offer. The decision rankled some in the game.

But it also highlighted a little publicized but growing income inequality in men's tennis that's not unlike the wealth disparity shaping political discourse across the country.

A USA TODAY analysis of the Association of Tennis Professionals prize money from 1990-2011 shows the wealth disparity between players ranked in the top 100 has never been greater. The study, which uses a commonly accepted method of measuring income distribution called the Gini co-efficient, also demonstrates that the gap has been greater over the course of the past three years than ever since the ATP's inception in 1990.

The prize money figures also include money earned at the four majors, which are not governed by the ATP.

Novak Djokovic, Rafael Nadal and Roger Federer, who have shared the top three ranking spots since 2007, have been more dominate in terms of prize money accumulation than any trio since the men's tour was formed more than two decades ago. They've raked in between 20% and 26% of available prize money the past five years. The only other trio ever to break 20% was Federer-Nadal-Andy Roddick in 2006.

The 20% mark had never been crossed before — not in the heydays of the Boris Becker-Stefan Edberg-Ivan Lendl or Pete Sampras-Andre Agassi-Jim Courier rivalries.

"It's really bad," says Michael Russell, 33, a veteran who has never ranked higher than No. 60 in his 14-year career. "It's been going on a long time. You look at the difference of a guy ranked 80 and a guy ranked 10. They are going to make a lot more money, but the differences are astronomical. Compared to other sports, it's not even close."

Recent prize money inequalities reflect an extraordinary era of dominance by the top three. Djokovic, Nadal, and Federer have won 11 of the past 12 majors and 17 of 27 Masters 1000 events, the biggest tournaments after the four Grand Slams.

"There's no doubt that the domination of top four (including Andy Murray) has impacted the distribution of prize money," said ATP CEO Brad Drewett, who looked the data Wednesday but said he could not offer much insight without further examination. "My instinct is that this chart reflects this domination rather than any other trend."

Their domination doesn't necessarily tell the whole story.

Several players decried the uneven weighting in latter rounds of events. At the BNP Paribas Open, for instance, the difference between runner-up and winner is $500,000, or half of the winner's prize.

"I have a little bit of a problem at tour events where winner gets almost double of what you make from finalist," American Robby Ginepri says.

Another factor that could be contributing to the wealth disparity is the slower pace of growth at the lower-tier Challenger level, since a portion of the top-100 players earn prize money from competing at these events.

From 1990 to 2011, total ATP prize money went from $33.8 million to $80.1 million in 2011, a 137% increase. Over the same period, total Challenger prize money barely doubled to $10.2 million from $4.9 million and even has fallen from a high of $12.3 million in 2008.

For those pros trying to break in, it can be tough to meet expense that includes travel, coaching, hotels and equipment.

"You just have to invest in yourself and pray to god that everything goes well," says Dennis Kudla, a 19-year-old American who lost to Federer in the second round. "There definitely is not enough money to have everything that these top guys have."

Not everyone sees it that way, however.

"People don't love tennis because of Challenger-level tennis," says fellow 19-year-old American Ryan Harrison. "People don't follow the Challenger players. It's a stepping stone that you know is a process you have to go through."

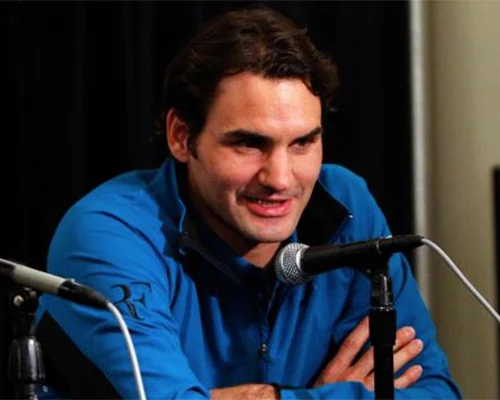

Federer, a 30-year-old with a record 16 major singles titles, is well aware of the building discontent among the rank-and-file. He is president of the Player Council.

He understands that it's more "sexy" to offer a big winner's check and that it's hard to say no when someone offers more money, strings or no strings.

Everyone, he says, has an equal shot to win it. But Federer isn't numb to the needs of players at the other end of the spectrum.

"I believe it's a winner's tour, so the money is there for everyone to play for," he said in a recent conference call. "But at the same time, we wish as well that the lower rounds would also get a bigger raise as well.

"Obviously it's an important task for the council and the board to make sure all the lower rounds get a bigger raise in the future."

Money has been front and center since the beginning of the year.

At the Australian Open, a chorus of discontent arose around what players see as the disproportionate amount of money being paid out by the four Grand Slam events, which operate independently from a financial standpoint. Regular tour events contribute 30% or more of revenues to prize money, while the four majors remain considerably lower — around 11-13%, players say.

That gap has generated strong emotions and calls work stoppages or other actions.

While extracting concessions from the majors is one issue, some are fighting to rectify what they see as wealth gap within the tour.

One of those is Sergiy Stakhovsky. The 76th-ranked Ukrainian has been one of the most vocal players behind the scenes, advocating a more even spread across all rounds at events.

"We are not interested in counting somebody's money," he says. "If somebody is winning it, he's winning it….But it should be equal."

Most players agree that the top players bring in fans and sponsorships and deserve a bigger cut of the pie.

"You can't really harp on the people selling the tickets of the sport that you're a part of," Harrison says.

But they also say that the money is too heavily skewed toward later rounds, especially when stars already receive guarantees - big sums paid out by tournaments organizers just to show up.

As veteran Russell says, "You need other guys to make up a whole tour just like in golf and other sports. It would be nice if it were spread around a little more. We need the top guys to stand up and help everyone else out a little bit more."

No one seems certain that there will be solutions anytime soon.

"It's like a Civil War going on inside of the sport," says Roddick, the 2003 U.S. Open champion. "I don't know that it's ever gonna work unless people put the best interests of the game ahead of the best interests of themselves. We don't have a history of doing that in tennis."

Contributing: Ryan Rodenberg