Winner Takes All

Elina Frumerman

Forty years ago this month marked seminal moments in the push for equality in women's tennis.

In September 1973, Billie Jean King defeated Bobby Riggs in the "Battle of the Sexes," and the U.S. Open for the first time awarded equal prize money to men and women.

But by one measure women's tennis has demonstrated a history of inequality when compared with men: among its own.

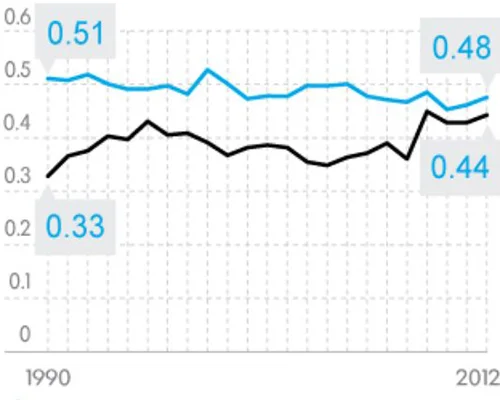

From 1990-2012, the relative distribution of prize money among the WTA's top 100 earners has, without exception, shown greater disparity when stacked up against the top 100 on the ATP Tour.

Another way of looking at it: The women's tour is more capitalistic.

"The statistical results indicate that the WTA's system more closely mirrors a winner-take-all payout scheme than their male counterparts," says Ryan Rodenberg, an assistant professor of sports law analytics at Florida State.

Rodenberg performed the prize money analysis using a widely accepted statistical model to measure income distribution called the Gini coefficient. A higher coefficient (up to 1) means less uniform distribution.

The data show that fewer women have earned a greater portion of the prize money pie and that the intra-tour wealth disparity has been more consistent (with less annual fluctuation than the men) over the course of the 23 years.

Many possible reasons

There are a number of possible explanations for the discrepancy.

One is the oft-cited contention that women's tennis is thinner from top to bottom than the men's game, otherwise known as competitive balance.

If true, it stands to reason that the crème de la crème are gobbling up more of the available dough.

Another explanation could be draw size.

The WTA fields more tournaments with first-round byes (for example, 28 or 30 players in a 32 draw), thereby protecting top seeds. The effect is likely minimal, but it could account for some difference.

Pam Shriver, a top pro in the 1970s and 1980s with a long history of governance participation in the game, offered another.

She says the disparity stems from a conscious historical precedent to build and legitimize women's tennis with winner-incentivized purses at a time of less status for women in the workplace and society.

"I would say prize money has been an overwhelmingly bigger marketing device in women's tennis than men's tennis," Shriver said.

Sam Stosur of Australia, the 2011 U.S. Open champion, echoed Shriver.

"So that's always going to be, at the end of the day, the ones that are in the finals, semis, whatever, they are the biggest rounds," said Stosur, ranked No. 17 but who has been as high as No. 4. "I think you have to reward those players for doing better.

"Of course everyone has to start somewhere. I have been in that boat starting on tour, and you need that first-round money to almost make it to the next event."

Differing formulas

Each tour, of course, has its own formula for how it breaks down prize money at tournaments among the different rounds. That's another point of discussion.

In looking at the prestigious Miami tournament in 2003, 2009, and 2012, which had the same format — a 96-player draw — every year for both men and women, Rodenberg found no meaningful change in prize money allocation.

That lessens the chance that the separate formulas are driving the gap.

The ATP counts 62 events compared with 58 for the WTA, which, according to young American Coco Vandeweghe, allows more earning opportunities for lower-ranked players.

Rodenberg said the Gini model accounts for such discrepancies and more tournaments should not affect distribution.

It's notable that the disparity has been converging over the past few years, primarily because the men have become less equal.

One explanation for that trend is the dominance at the top of the game. Novak Djokovic, Rafael Nadal, Andy Murray and Roger Federer have won 34 of the past 35 majors, which offer the biggest prize money by far.

By contrast, 14 women have won majors during the same period.

That growing disparity sparked the vocal push from the men to increase prize money in earlier rounds at Grand Slam tournaments. All four responded with higher percentage increases for early-round losers.

Worth exploring

When shown the Gini calculations, women's tour officials responded with a statement: "The WTA seeks to strike a balance between rewarding tournament winners and those who succeed in winning multiple rounds, while ensuring that players who make it into the main draw and early rounds of our events are also able to be appropriately compensated as professionals."

The USA's Bethanie Mattek-Sands, who represents players ranked 100 and above on the WTA Player Council, said the findings were worth exploring.

"I'd be interested in taking a statistic like that, real numbers, and sitting down with (WTA CEO Stacey Allaster) and everyone else that makes these decisions for women," she said. "Obviously we want to reward winning. That's most important. But at the same time we want girls who are around 100, 80, 60 who are still great players to be able to pay their bills and their coaches. I'm a firm believer in that."

With a couple of exceptions, 45th-ranked Mattek-Sands said the council has agreed with the men's efforts for more equal distribution at majors. Though she had not seen the figures, she said perhaps the same applies to the women's tour.

"The numbers don't lie," she said. "We can say this and that and look at people's prize money, but if you bring solid numbers with research and facts and if something is a little off, I think it's feasible to see it change."