The Man Behind Serena's Surge

Elina Frumerman

NEW YORK — It started as a typical pro circuit acquaintance: Casual greetings, chats by the practice courts or conversations at tournaments.

In crisis, it became a partnership, and much more.

Fifteen months after Patrick Mouratoglou lent a hand to Serena Williams — then reeling from her first opening-round loss at a major — he has become the catalyst behind her return to the top of women's tennis.

Part guru, part promoter, presumed paramour and unquenchable tennis junkie, the 43-year-old Frenchman has gradually become part of the tight-knit inner circle of the Williams team — and, by most accounts, her heart as well.

"We have this great communication," Williams told USA TODAY Sports after winning her second French Open in June. "It's definitely a two-way street. I think coaches sometimes think it's always their way. And it's like, 'You do this because I say it.' Our dynamic is not like that at all. I think that's what makes him so good. He's open to me, and I'm open to him. It creates something special."

Since teaming up after last year's French Open, Williams, 31, has put together the most complete winning stretch of her career.

She captured Wimbledon, Olympic, U.S. Open, and French Open titles and has compiled a 95-5 match record, the best of any stretch during her 17-year career.

This period, which includes a personal-high 34-match winning streak in the spring, compares favorably with her dominant 12 months of 2002-03, when the American won four consecutive majors (but fewer matches and titles), the so-called Serena Slam.

As top-ranked Williams looks to defend her U.S. Open crown and notch a 17th Grand Slam title, no figure is more important than Mouratoglou. She takes on Carla Suarez Navarro, the No. 18 seed from Spain, in Tuesday's quarterfinals.

Mouratoglou sat down with USA TODAY Sports this summer to discuss the "very complex" personality of Williams and their evolving relationship, which he likened to becoming conversant in another tongue.

"If you just stick to what she says, you'd be wrong most of the time," he said. "You have to understand what's behind all of the time. You have to anticipate."

"You have to learn another language," he added.

Tennis was 'my life'

The eldest son of a Greek-born business mogul, Mouratoglou was a middle-rung junior player with professional aspirations who gave up the sport at 15 at his parents' behest to concentrate on school.

"My reality was that I would become a tennis player," says Mouratoglou, who whose mother is French. "I never had any doubt about it. It was my life."

He didn't touch a racket for seven years. Groomed to take over his father's company — one of the largest renewable energy firms in France — he instead quit at 26 to begin building a tennis academy on the outskirts of Paris.

Mouratoglou says it was a tough conversation, but his father took it well and supported his decision.

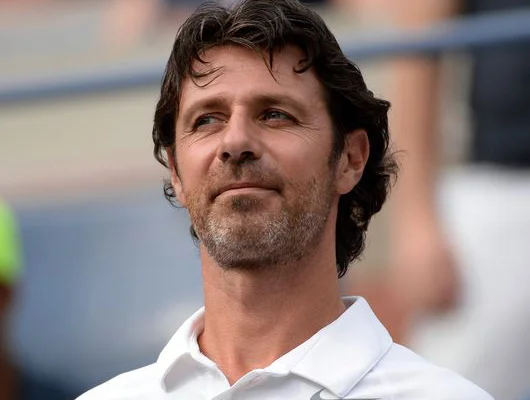

Patrick Mourataglou, the coach of Serena Williams, signs an autograph at the U.S. Open. "We have this great communication," Williams says. (Photo: USA TODAY Robert Deutsch-USA TODAY)

Mouratoglou told his father he enjoyed business, but it didn't touch his soul.

"I told him, I'm sorry," he said. "It is interesting, but it's not a passion for me, and I need passion in my life ... I really need my freedom."

His peers were dumbfounded.

"When I said to my friends I want to become the best coach in the world and win Grand Slams with players, they said to me, 'You are crazy, you don't know anything,' which was true."

Mouratoglou was a quick study. He rented land and gradually built his fledgling tennis dream into one of the biggest private academies in Europe.

Several successful players have passed through it, among them top-30 players Grigor Dimitrov, Jeremy Chardy, Anastasia Pavlyuchenkova and Aravane Rezai. Martina Hingis recently helped coach there.

Mouratoglou does not deny that his motivation to make something of himself stems from frustration about his own stunted tennis ambitions.

"I think it's the best motor in life," he says.

Unvarnished opinion

When Williams crashed out in the first round at last year's Roland Garros to 111th-ranked Virginie Razzano, she needed a place to practice and reached out to Mouratoglou. Williams already owned an apartment in Paris' 7th arrondissement, and soon she was heading out to train with Mouratoglou daily.

Williams, Mouratoglou says, asked for his unvarnished opinion of the Razzano match, which Williams had several chances to close out before losing in three sets.

He told her she appeared emotionally uptight and often off-balance in her movements.

Serena Williams of the USA celebrates after defeating Maria Sharapova of Russia 6-4, 6-4 to win the French Open. (Photo: Susan Mullane, USA TODAY Sports)

"I didn't know why she was like that, but I was shocked," he said of the 16-time major champion.

The relationship quickly blossomed.

Mouratoglou took on an informal role and accompanied Williams to Wimbledon, where she won her fifth championship. Her form continued through the summer with wins at the London Olympics and the U.S. Open.

There is little doubt Williams has become a more complete player.

She remains the best server in the women's game, but has improved statistically in nearly every return metric this year, from break points converted to points won returning first serve.

That was clear in her emphatic 6-4, 6-1 fourth-round defeat of No. 15 seed Sloane Stephens on Sunday. Her court coverage and defensive play wore the 20-year-old American down as much as her vaunted power.

"She is mutating," Mouratoglou says. "If you look at how she was playing when she was 20 and now, it's a completely different player."

'You have to break the walls'

Working with Williams has meant learning to read her moods. Just as important is integrating with her longstanding entourage.

"You have to break the walls to get in," Williams said.

"I just think in general we are kind of close, so it's never easy for the new person," she added. "Me, I'm always like, C'mon! It's everyone else that is so protective."

Isha Price, Williams' half-sister and frequent travel companion, says the process is ongoing.

"When you introduce a new member or something different it's a situation where you are still looking for that rhythm and how that person will fit into the mix," she said.

Though fluent in English, there have been cultural barriers and benefits.

He has helped Williams with her emerging French, which she showed off in on-court interviews at the French Open. She has taught him the joys of eating fast food in a car. Mostly they laugh off any awkwardness.

"American and French culture are really, really different, but in a way it's funny," says Mouratoglou, who admires what he calls the USA's "winning culture."

If he seemed tentative to partake in the post-match festivities at Wimbledon last year in his first tournament as informal adviser, after his victory in Paris Mouratoglou shared hugs and celebrated openly with Williams' family and inner circle.

On the issue of the growing dimensions of their relationship, both have been coy, evasive or silent.

Neither would comment to USA TODAY Sports about it. But paparazzi have caught the couple in various cozy poses over the past year.

Mouratoglou has three children ages 10, 12 and 19. He is separated from his wife but is not yet divorced.

"It's on the way," he said.

Not everyone is a fan

Mouratoglou has bright, intense eyes, dark hair and a cropped beard with patches of gray. Chatty and ambitious, he consults for Eurosport, writes a blog and prominently lists himself as Serena Williams' coach on his Twitter profile. She is front and center on his academy website.

Mouratoglou does not tend to look back.

Several years ago, he underwrote a talented 5-year-old American, who relocated with his family to live and train at his academy. (USA TODAY Sports wrote a 2007 profile on the student, Jan Silva.) The parents ended up in a messy custody battle and divorce. He said he has no regrets about what some saw as a risky bet on a young child, who is no longer with the academy.

Marcos Baghdatis fell behind early against Stanislas Wawrinka. (Photo: Anthony Gruppuso, USA TODAY Sports)

He has detractors, too.

In January, former top-10 player Marcos Baghdatis of Cyprus scoffed at the idea Mouratoglou contributed much to a player with 14 Grand Slam titles when they started working together.

"I don't think it changed too much in her game," said Baghdatis, who spent his teenage years at Mouratoglou's academy and was Mouratoglou's breakout student before ultimately severing ties. "I think she's a great player, and he's lucky to be there."

Asked about him last week before he lost in the third round at the U.S. Open, Baghdatis said: "I tried to work with him, and it didn't work out. I don't like the way he worked. I don't really want to talk about it."

Mouratoglou does not shy away from self-promotion and sometimes falls victim to what in today's parlance some call humble brag.

"I think I had a lot of impact on every player," he said. "Maybe it sounds cocky, but if I don't feel I have an impact or a big impact, I wouldn't be able to be excited about my work every day."

But players that have worked with Mouratoglou describe him as an astute, dedicated coach who is "in love" with tennis.

"He put tennis as a priority before everything," said Rezai, a former top-15 player from France.

Victor Hanescu, a Romanian who has used his academy as a base for the past year and a half, says he "can't see another explanation" for Mouratoglou's chosen profession but for his love of the game.

"He has a rich family and he can do of course many things," Hanescu says.

Agrees Mouratoglou: "Since 6 years old I am completely obsessed."

Williams values commitment

Mouratoglou says he tailors his style based on what players need, whether it's strategy, fitness or mental toughness. He likens himself to a medical doctor that is both "generalist and specialist."

He is proud of his association with Williams, which he compared to coaching Real Madrid or Manchester United in soccer because it means he is at the top of his profession.

Williams said they found an immediate coaching connection because Mouratoglou thinks like her father, Richard, who taught her the game.

"That's the only reason I was able to work with him — because of that mind frame," she said. "We have the same forward way of thinking."

Despite her accomplishments, Mouratoglou says Williams can be hardheaded and stubborn but is open to ideas and always willing to improve.

She values commitment.

"He seemed to be 100% with whoever he was with," Williams said. "If I want to work with someone, I want that kind of loyalty."

Mouratoglou sounded philosophical when asked about the road ahead. He plans to continue coaching others when Williams hangs up her rackets, or if they part ways earlier.

"You know," he said, "she takes what she wants from me, and she probably takes also from other people like her father, her mother, all those things. So it's teamwork. What is important is at the end of the day she's winning and she's successful. That's what we all want."