The Wizard of Post-Match Chat

Douglas Robson

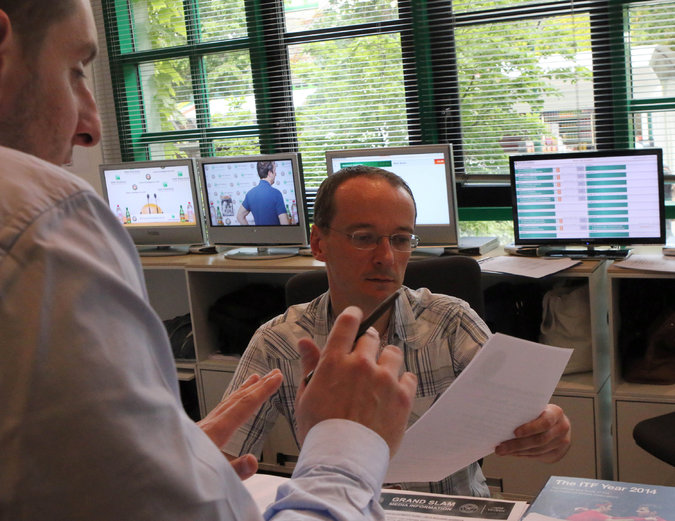

Nick Imison relies on pencil and paper, among other tools, to help him track thousands of interviews at the French Open.

PARIS — The yellow brick road of interviews leads to Nick Imison.

Need postmatch face time with Roger Federer? Rafael Nadal? Serena Williams? Imison can grant your wish.

Imison operates not behind a curtain but tethered to his desk. His tools: pencil, sharpener, paper, ruler, eraser, highlighter, Blackberry, landline and walkie-talkie, to which his ear is continually glued. And tact. Most of all, tact.

A member of the International Tennis Federation’s communications department, Imison coordinates thousands of mandatory and elective interviews during the two weeks at the French Open. He does the same at the Australian Open and the United States Open.

He deals with emotional players like Venus Williams, who skipped her required postmatch news conference after a first-round loss to Sloane Stephens on Monday.

He also is the messenger of news, good and bad, about whether a one-on-one interview request has been approved.

The London-born Imison handles it all with a stereotypically stiff upper lip.

“You learn not to take it personally,” he said.

Part air traffic controller, part gatekeeper, part envoy, Imison is the leader in a hive of news media activity. In Paris, he operates tucked behind a small waist-high barrier inside the French Open’s media center.

His job, he says, is to “liaise” with players, agents and international news media. But it is so much more.

He supervises the runners who relay media requests and escort players for interviews. He determines which player goes into what interview room, and for how long. He deals with reporters on deadline, agents concerned about media overload and players in a variety of postcompetition moods. He delegates, prioritizes and negotiates.

He does all this as swarms of matches finish throughout the day.

At full bore, Imison checks scores, emails from his phone, fields requests from journalists, barks on his radio and sometimes scampers to check on available interview rooms.

It is a mind-bending exercise in parallel channels of attention — multitasking at the highest level.

“I feel like he probably has 80 people talking to him at once,” the player Madison Keys said. “But he always seems so in control of the situation.”

At the four majors, all players are required to meet with reporters after matches, if requested, or face fines of as much as $20,000.

With ego, ranking points and money on the line — and fresh off the heat of competition — they can be problematic, testy and evasive.

Some do not show up. Some have tried to hoodwink runners by pretending to be someone else. Some resist.

Imison, on occasion, will threaten players with fines if they neglect to meet basic news media duties.

That prompted one recalcitrant player to liken him to a totalitarian regime.

“This is a dictatorship,” the player hollered.

Some, like the seven-time major winner Venus Williams, are unmoved.

“In terms of negotiation, it was quite straightforward,” Imison said of Williams, who was fined $3,000 by the International Tennis Federation for her infraction. “She understood that she faced a fine.”

On the flip side, players demonstrate professionalism and decorum.

Imison remembers the time the 2003 French Open champion Juan Carlos Ferrero of Spain trudged into the interview room unescorted after a loss and sat alone for several minutes. Nobody noticed.

“I didn’t realize he was in there until I saw him on the screen,” Imison said.

The conflicting nexus of demands also creates comical cross-cultural situations.

Once, a runner brought in the wrong Japanese player, but the assembled journalists were too polite to point out the error. They interviewed the player, then returned to Imison’s desk.

“Are you going to bring up Ayumi Morita now?” they asked.

A bespectacled wisp of a man, Imison, 45, is a tennis lifer.

He grew up in southwest London near Queen’s Club, where the British Lawn Tennis Association was once based. At 19, he deferred college to take an internship with the association, which then offered him a full-time job. He never returned to school.

He then bounced around the tennis media world, including stints with the men’s and women’s tours, before he was hired by the International Tennis Federation, which provides media staff at Grand Slam events.

Imison, who is single, spends about 16 weeks on the road a year and has been in his current role since 2002.

Dressed in khakis and a button-down shirt, he begins his day by organizing media requests into a “master” spreadsheet. He does this by hand, with a pencil, ruler and paper. He uses a system he inherited from his predecessor.

“It’s simple but effective,” he said.

On the most dizzying days, Imison and his crew handle hundreds of interviews. They include players in singles, doubles, mixed doubles and juniors.

“The first four days are crazy, but when you have second-round singles with first-round doubles, it can be insane,” he said.

After a rainout at the French Open in 2007, Imison coordinated 131 mandatory interviews on the first Tuesday — 91 men and 40 women.

“I think every man still left in the tournament played that day,” he said.

The French Open is the busiest major because it allows nonrights-holding broadcasters to film one-on-one interviews.

Last year’s French Open set a tournament record: 717 requests filled over 15 days, or nearly 48 per day.

But that does not include dozens and dozens of nonmandatory individual interviews. Imison estimates the two-week total at nearly 2,500.

“It does test my multitasking abilities,” he said.

During crunchtimes, Imison barely leaves his desk. His colleagues carry meals to him. During 12- to 14-hour workdays, Imison even takes his walkie-talkie to the restroom, he said.

Besides postmatch news conferences, reporters can ask for one-on-one interviews. Players do not have to concede. That is when Imison’s job also gets tricky.

Often, he must convey that a request has been given or denied for nonmandatory requests. He does this on his master sheet with a circle (accepted) or a cross (declined or no longer applicable, for example, if a player was requested only after a win, but lost).

If a journalist wants a player for 15 minutes but the player offers only five, Imison will aim for the middle. He tries to spread the wealth. He does not discriminate.

“I take a one-on-one request for a doubles player from a Slovenian journalist as seriously as multiple requests for Roger Federer from international broadcasters,” he said.

If an individual request has little likelihood of materializing, Imison is upfront.

“If there is no chance, I will sometimes advise them to request a different player rather than just go through the motions,” he said.

Imison must be a United Nations-caliber expert in handling complex names — Thailand’s Noppawan Lertcheewakarn does not roll off the tongue — and navigate a variety of customs and social mores befitting one of the most global sports.

Runners — local residents hired, sometimes year after year, to grab players and usher them to interview rooms — are another challenge. They come from all walks of life; among them are tour guides, law students and even a standup comedian.

Wimbledon is the sole Grand Slam where interviews are handled in-house. As a result, Imison experiences phantom vibration syndrome.

“I keep thinking I’ve lost my walkie-talkie, and then I realize I don’t need one,” he said.

Despite the long hours, scheduling calculus and personality juggling act, Imison seems preternaturally upbeat. Perky, almost. One could say he has mastered a British social grace well suited for his position: polite but firm.

“He has an incredibly hard job, but he does it with a smile on his face and a wonderful disposition,” said Federer’s agent, Tony Godsick.

Imison, emphasizing the team nature of his work, modestly says he gets a “buzz” out of facilitating as many one-on-one interviews as possible.

Ultimately, he has no magical power to grant interviews.

“There are days I am in the firing line for their disappointment,” he said of reporters. “Most tennis media understand that I try to be fair.”